Talk about childcare: this bird has figured out a way around that.

The brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater) is a well-known North American native bird found throughout the United States, northern Mexico and most of Canada. They also are a very well-known obligate brood parasite.

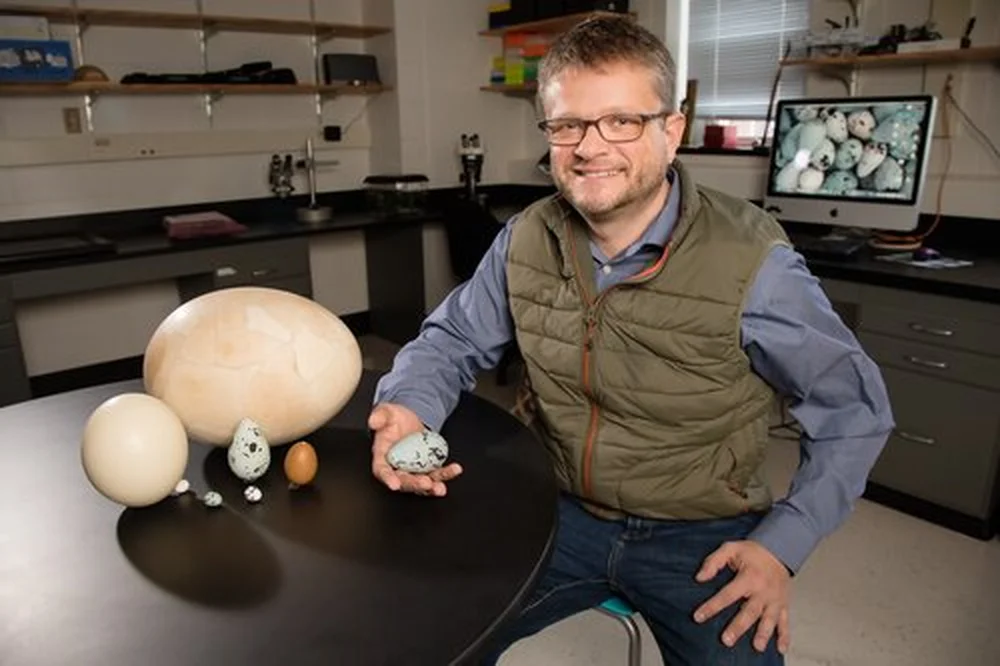

So what exactly is brood parasitism and how did this peculiar behavior come about? Basically, it means laying your own eggs into the nests of others. According to Dr. Mark E. Hauber, ornithologist and professor in integrative biology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, brood parasitism is carried out by multiple species including birds, fishes and social insects such as termites, wasps, bees, ants and beetles.

But cowbirds remain one of the best-known examples. What is really going on with cowbirds?

When it comes to this species, brood parasitism likely originated due to high rates of nest predation, where individual females who lost their clutch to predation during the egg laying stage had “spare” eggs to lay and benefited from sneaking these eggs into the nests of other individuals or even other species.

The act of brood parasitism allows females to forgo the costs of nest building, incubating eggs, and feeding and protecting vulnerable young. Instead, they can invest their energy on laying more eggs per season.

“There is a cost of parasitism, though,” says Hauber. “Many hosts attack and potentially harm brood parasitic adults, occasionally killing them.”

To see brood parasitism in action has been an amazing thing for some researchers. Dr. Desirée L. Narango, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, describes her experience with cowbirds while she was a master’s student at Ohio State University studying and monitoring northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) and Acadian flycatcher (Empidonax virescens) populations.

“In Ohio, cardinals start breeding from mid-March until late August,” she says. “In order to monitor populations, we have to find a lot of nests. Cardinals put their nests in predictable locations such as dense shrubs and saplings, so they can be pretty easy to find once you get a search image for them.”

As Narango and her team carried out nest searches, they were careful to not make the nest locations more obvious to predators like raccoons and blue jays. In those urban and rural forest fragments, cowbirds were also abundant.

Read more: Cool Green Science