Information about the Human Memory and Cognition Lab

The Human Memory and Cognition Lab uses empirical, computational, and developmental approaches to understand how memory works in humans. As the principal investigator, Aaron S. Benjamin, puts it, “The goal of our research is to understand memory use in the larger context of skilled performance—by specifying a minimal set of operations that operate in service of translating experience into memory, and vice-versa, and then exploring the flexibility of how these basic operations are used by the cognitive system as a whole.” This is explored in the subtopics of memory skill, recognition, metacognition and memory, aging and memory, language and memory, and reminding.

The Human Memory and Cognition Lab uses empirical, computational, and developmental approaches to understand how memory works in humans. As the principal investigator, Aaron S. Benjamin, puts it, “The goal of our research is to understand memory use in the larger context of skilled performance—by specifying a minimal set of operations that operate in service of translating experience into memory, and vice-versa, and then exploring the flexibility of how these basic operations are used by the cognitive system as a whole.” This is explored in the subtopics of memory skill, recognition, metacognition and memory, aging and memory, language and memory, and reminding.

Our principal investigator is Dr. Aaron S. Benjamin.

Please open the tabs at the bottom to learn more about our research topics or visit at our website here.

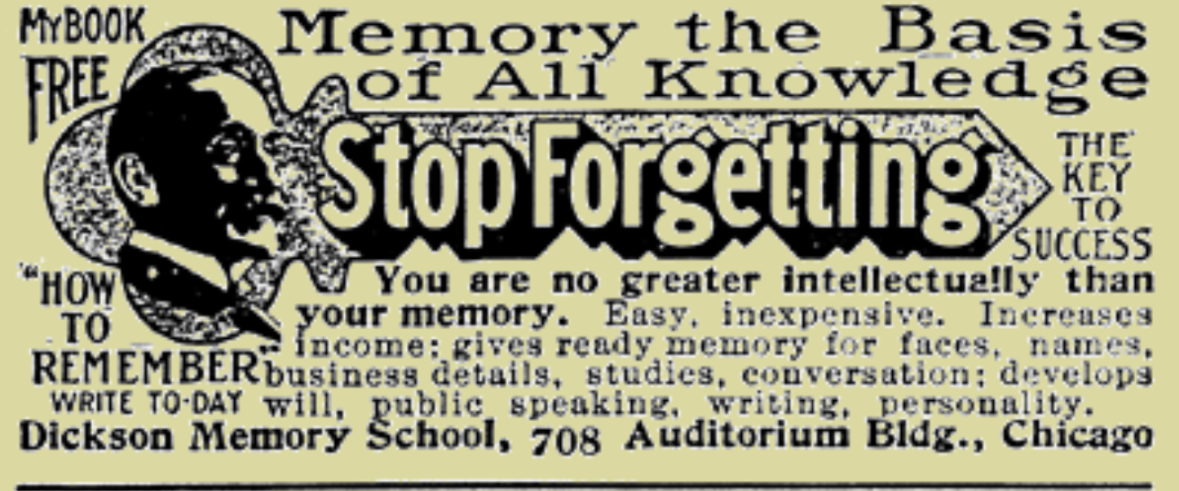

Memory Skill

Remembering a fact, a phone number, or how to play racquetball reveals the contribution of more than the act of memory. Strategic decisions must be made about how to encode information, how to maintain those stores of knowledge, how to effectively access that information when it is needed, and how to assemble that information into a coherent decision or output. Such dimensions of "memory skill" unite the lab's research on memory--in which we examine basic mechanisms underlying remembering and forgetting--and the research on metamemory, in which we examine the monitoring and control processes that subserve decisions about memory.

Memory and Decision Making

We use recognition memory and related tasks as a test bed for developing computational models of memory decisions. In one line of work, we extend decision models based on signal-detection theory to include variable decision noise and to describe more varied memory tasks, including multivariate tasks that involve multiple memory decisions. For example, querying memory for an event often involves attempts at retrieving information about the event itself (item memory) as well as information about contextual details accompanying that event (source memory) -- such as the gender of a speaker, the color a word was printed in, or the physical surroundings of a pictured object. We also develop process models of recognition judgments in order to test how global deficits in memory fidelity can yield selective deficits on empirical tasks such as source memory judgments.

Metacognition and Metamemory

Efficient memory use requires accurate metamemory: the processes that monitor states of learning, knowledge, and skill, and also control the deployment of mnemonic and other cognitive processes to achieve desired states. That is, one must be able to make accurate judgments about one's current memory state and predictions about future states, and exercise judicious control over the various options at one's disposal, including encoding and retrieval strategies, study time allocation, item selection, and scheduling of study repetitions. Our research investigates the monitoring and control processes that comprise metamemory by focusing on factors that moderate metamemory performance, such as prior knowledge, task goals and expectations, time pressure, and stimulus characteristics. For example, we are interested in the conditions under which one exhibits "learning to learn" i.e. adaptively calibrating metamemory in order to more effectively assess and deploy memory resources in the context of a specific task. Our interests also concern the development of ever more sophisticated and rigorous approaches to the analysis and measurement of metamemory.

Aging and Memory

The human memory system is constantly changing and adapting throughout the lifespan. Some of these changes result because of the ever-growing body of knowledge and experience acquired over a lifetime. The system has to adapt to maintain fluent access to an ever-growing knowledge base. Other changes occur in order to compensate for biological changes that occur with aging. The goal of our research is to understand what aspects of memory and metamemory change across the lifespan and to understand what aspects remain the same. Our basic perspective is that aging involves a global deficit in memory that reveals a landscape of the relative resistance of tasks to disruption. Further, we investigate changes in older learners’ metamnemonic monitoring and how older learners compensate (or fail to compensate) for changes in memory ability through the use of metamnemonic strategies and behaviors.

Reminding

By bringing relevant knowledge to bear in novel circumstances, remindings allow us to thrive in a complex and ever-changing world. Remindings play a significant role in higher cognition (e.g., problem-solving, understanding, generalization, classification, and number representation), but their role in memory has largely been ignored. We have proposed a reminding theory arguing that remindings play a fundamental role in memory, underlying the effects of both repetition and spacing (Benjamin & Tullis, 2010). We are currently investigating hypotheses derived from reminding theory concerning remindings' basic mnemonic effects. Preliminary results hint that remindings enhance the memory for individual instances in associated pairs, as predicted by reminding theory. Reminding may be an effective technique to capitalize on the innate strengths of the human memory system while minimizing the efforts learners must expend.

Language and Memory

The goal of our research in language and memory is to understand how linguistic cues can influence memory for words, sentences, or larger texts. Words contain both semantic information (meaning) and surface form information (the letters or sounds in the words), and these different kinds of cues may remind us of different information or be forgotten at different rates. Another important cue is the emphasis placed on particular words. For example, if a speaker emphasizes the word “NEWSPAPER” in the sentence “The NEWSPAPER won an award for covering the fire,” we may focus our memory on different information (that the newspaper won the award, rather what the award was for) or even bring to mind different ideas (who else might have won the award instead of the newspaper?). Our general view is that linguistic contexts can powerfully influence encoding strategies, which in turn affect memory performance.

Memory for Faces

The ability of humans to recognize the faces of recently encountered individuals has generated a vast amount of research. Surprisingly, there is almost no research examining whether we are able to make accurate predictions about our own ability to recognize faces. A well-replicated finding is that people are better at recognizing faces more like their own—their own race, their own age—relative to faces from other groups. We are interested in examining the cognitive and metacognitive processes underlying this bias in face memory: Do people spend less time studying other-race faces relative to own-race faces? Are predictions about later recognition more accurate for own-race faces than for other-race faces? Can individuals use metacognitive information to change their encoding strategy and improve recognition of other-race faces? We are also examining how social information can bias the encoding and recognition of ambiguous race faces.